Example: Orbit Raising

Difficulty: Intermediate

The problem was originally presented by [1].

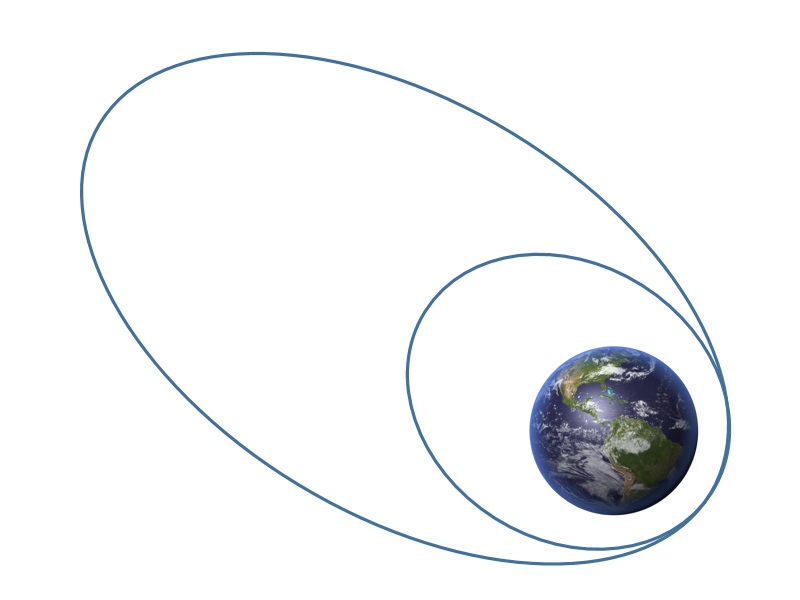

Consider the orbit transfer problem illustrated below

The objective is find the optimal control profile such that radius of the final orbit is maximized:

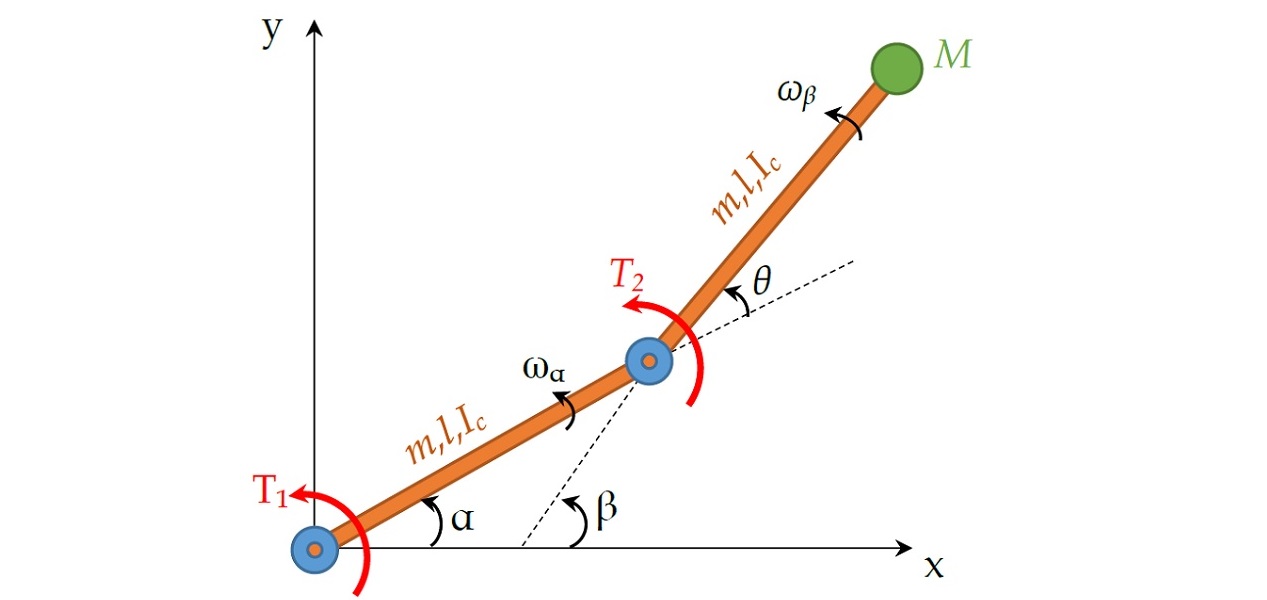

With scaling and nondimensionalization (e.g. using Astronomical unit), system dynamics can be expressed as

with

Additionally, we have path constraint,

simple bounds on variables,

and boundary conditions

We require the numerical solution to fulfill the following accuracy criteria

Formulate the problem in ICLOCS2

In internal model defination file OrbitRaising_Dynamics_Internal.m

We can specify the system dynamics in function OrbitRaising_Dynamics_Internal with

r=x(:,1);theta=x(:,2);v_r=x(:,3);v_theta=x(:,4);

u_1=u(:,1);u_2=u(:,2);

T1=vdat.T1;

md=vdat.md;

dx=[v_r,v_theta./r,(v_theta.*v_theta)./r-r.^(-2)+(T1./(1-md*t)).*u_1,...

(-v_r.*v_theta)./r+(T1./(1-md*t)).*u_2];

g_eq=u_1.*u_1+u_2.*u_2-1;For this example problem, we have one equality path constraints, so function OrbitRaising_Dynamics_Internal need to return the value of variable dx and g_eq .

Similarly, the (optional) simulation dynamics can be specifed in function OrbitRaising_Dynamics_Sim.m .

In problem defination file OrbitRaising.m

First we provide the function handles for system dynamics with

InternalDynamics=@OrbitRaising_Dynamics_Internal;

SimDynamics=@OrbitRaising_Dynamics_Sim;The optional files providing analytic derivatives can be left empty as we use finite difference this time

problem.analyticDeriv.gradCost=[];

problem.analyticDeriv.hessianLagrangian=[];

problem.analyticDeriv.jacConst=[];and finally the function handle for the settings file is given as.

problem.settings=@settings_OrbitRaising;Then we may define the time variables with

problem.time.t0_min=0;

problem.time.t0_max=0;

guess.t0=0;and

problem.time.tf_min=3.32;

problem.time.tf_max=3.32;

guess.tf=3.32;For state variables, we need to provide the initial conditions

problem.states.x0=[1 0 0 1]; bounds on intial conditions

problem.states.x0l=[1 0 0 1];

problem.states.x0u=[1 0 0 1]; state bounds

problem.states.xl=[0 0 0 0];

problem.states.xu=[2 pi 2 2]; bounds on the absolute local and global (integrated) discretization error of state variables

problem.states.xErrorTol_local=[0.01 deg2rad(0.01) 0.01 0.01];

problem.states.xErrorTol_integral=[0.01 deg2rad(0.01) 0.01 0.01]; tolerance for state variable box constraint violation

problem.states.xConstraintTol=[0.01 deg2rad(0.01) 0.01 0.01]; terminal state bounds

problem.states.xfl=[0 0 0 0];

problem.states.xfu=[2 pi 2 2]; and an initial guess of the state trajectory (optional but recommended)

guess.states(:,1)=[1 1.4];

guess.states(:,2)=[0 2.5];

guess.states(:,3)=[0 0.05];

guess.states(:,4)=[1 0.8]; Lastly for control variables, we need to define simple bounds

problem.inputs.ul=[-1 -1];

problem.inputs.uu=[1 1];bounds on the first control action

problem.inputs.u0l=[-1 -1];

problem.inputs.u0u=[1 1]; tolerance for control variable box constraint violation

problem.inputs.uConstraintTol=[0.01 0.01]; as well as an initial guess of the input trajectory (optional but recommended)

guess.inputs(:,1)=[0.4 -0.7];

guess.inputs(:,2)=[.9 0.7];We need to specify the bounds for the constraint functions . We have one equality path constraint

problem.constraints.ng_eq=1;

problem.constraints.gTol_eq=[0.01];but do not have any inequality path constraint

problem.constraints.gl=[];

problem.constraints.gu=[];

problem.constraints.gTol_neq=[];Additionally, we have two boundary constraint functions

problem.constraints.bl=[0 0];

problem.constraints.bu=[0 0];

problem.constraints.bTol=[1e-02 1e-02];We may store the necessary problem parameters used in the functions

problem.data.T1=0.1405;

problem.data.md=0.0749;Since this problem only has a Mayer (boundary) cost , and no Lagrange (stage) cost ,we simply have

boundaryCost=-xf(1);stageCost = 0*t;for sub-function E_unscaled and L_unscaled respectively.

For this example problem, we do have two boundary constraints (in addition to varialbe simple bounds). Thus we need to specify sub-routines b_unscaled as

bc=[xf(4)-sqrt(1/xf(1));xf(3)];Main script main_OrbitRaising.m

Now we can fetch the problem and options, solve the resultant NLP, and generate some plots for the solution.

[problem,guess]=WindshearGoAround; % Fetch the problem definition

% options= problem.settings(5,8); % for hp method

options= problem.settings(20); % for h method

[solution,MRHistory]=solveMyProblem( problem,guess,options);

[ tv, xv, uv ] = simulateSolution( problem, solution, 'ode113', 0.01 );Note the last line of code will generate an open-loop simulation, applying the obtained input trajectory to the dynamics defined in WindshearGoAround_Dynamics_Sim.m , using the Matlab builtin ode113 ODE solver with a step size of 0.01.

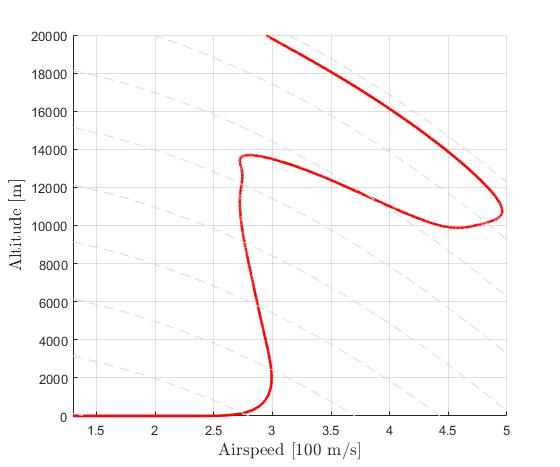

Results from ICLOCS2

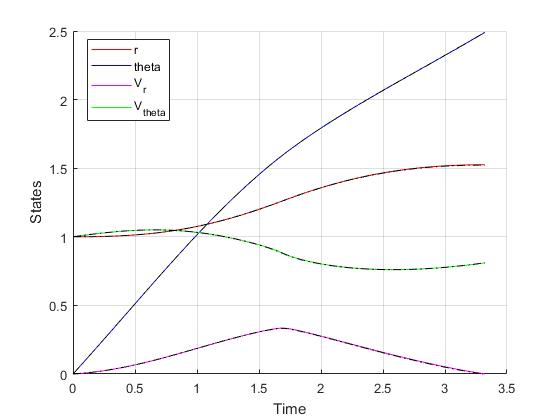

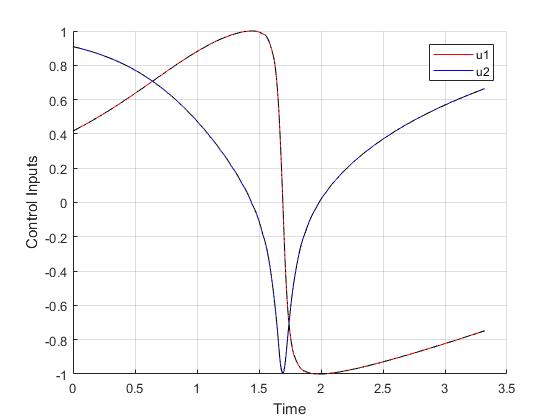

Using the Hermite-Simpson discretization scheme of ICLOCS2, the following state and input trajectories are obtained under a mesh refinement scheme starting with 40 mesh points. The computation time with IPOPT (NLP convergence tol set to 1e-09) is about 12 seconds for 2 mesh refinement iterations together, using finite difference derivative calculations on an Intel i7-6700 desktop computer. Subsequent recomputation using the same mesh and warm starting will take on average 0.5 seconds and about 20 iterations.

Converting the nondimensionalized time variable back yield

which is equivalent to a journey time of approximately 193 days.

Alternative Formulation

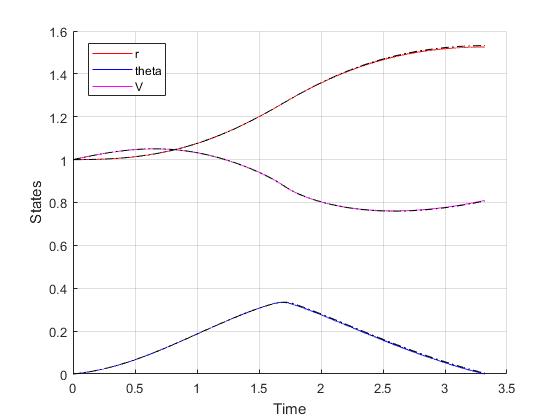

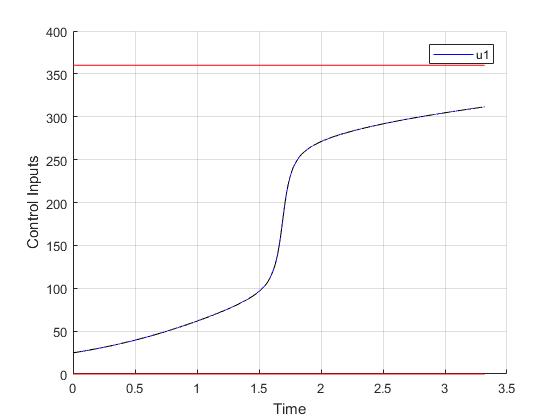

Optimal control problems that are mathematically equivalent may yield different results in compuatational efficiency. Here we demonstrate the benefit of using an alternative formulation of the same orbit raising problem. Instead of using the two elements of the direction vector as control input, we can reformulate the problem that directly uses the directional angle as control inputs. In this way, we can reduce the number of states and inputs by 1 each, and also eliminate the need of one equality path constraint. In addition, faster computations can be obtainable using analytic derivatives infomation rather than finite difference computations.

As the result, using the same Hermite-Simpson discretization with the same 40 mesh points at start, the following state and input trajectories are obtained after refining the mesh 2 time as well. The computation time with IPOPT (NLP convergence tol set to 1e-09) is now reduced to just 1.4 seconds . Subsequent recomputation using the same mesh and warm starting will take on average 0.3 seconds and less than 20 iterations.

[1] A.E. Bryson, and Y.C. Ho, Applied Optimal Control, Hemisphere Publishing, New York, 1975.